Known as ‘the English Merlin’ to his friends and ‘that juggling Wizard and Imposter’ to his enemies, William Lilly was one of the most well-known and revered political astrologers of 17th century England, who led a colourful life during socially transitional and politically volatile times.

The Mystic Meg of his day, Lilly was one of the first conventionally popular astrologers, his fame facilitated by the advent of the printing press and the temporary abolition of censorship laws during the English Civil War and Cromwell Years, which led to a more permissive environment that encouraged more open public discussion and political debate.

In this extract from episode six of the Astro-Insights podcast, I look at how freedom of the press aided Lilly’s rise to prominence but would eventually also make it personally hazardous for him to make public predictions, especially if they were not favourable to those in positions of power. An egalitarian and supporter of the populist Parliamentarian cause, Lilly would eventually become disillusioned with the political process and come to agree with his royalist friend, Elias Ashmole, that perhaps sharing too much knowledge, especially with the judgemental, overly-excitable or those with vested interests, was potentially foolhardy. Given the parallels between the English Civil War and the current geopolitical climate, I thought his experiences might potentially offer us some insights that could prove instructive or illuminating.

William Lilly and Elias Ashmole lived during an age of enormous cultural and political shifts when traditional institutions and all forms of authority, knowledge and expertise were being questioned. This was also a time of social chaos, of regular plagues and epidemics, as well as destructive fires when not just the zeitgeist, but the very fabric of people’s lives, including their homes and families, were constantly being torn down and remade. Not only was this anxiety-producing, as evidenced in the dramatic rise of apocalyptic tropes and alternative religious movements, but it also produced a plethora of opportunities for those adaptable and courageous enough to take a few risks.

And in many ways, it was Lilly’s ability to capitalise on this chaos and political turmoil that would make him famous and successful. Thanks to his well-placed natal benefics, Lilly was also very good at cultivating longstanding connections with people in high places, which certainly helped him to attract wealthy and influential patrons, not to mention escape several scrapes with the law.

However, lucky timing was another factor at play: Lilly came to prominence just as censorship laws in England were being relaxed, and the printing press as a means of mass communication was taking off.

Encouraged by his mentor Sir Bulstrode Whitelocke, William Lilly published his first astrological almanac in April 1644, marking the beginning of what would become an annual tradition. From the outset, his pamphlets and almanacs captured widespread interest. Carefully crafted to appeal to a broad audience, they combined astrological prognostications with sensational storytelling, featuring real life accounts and celebrity insights, all interpreted through the lens of astrology.

Lilly, who was both well-informed and a bit of a raconteur, was meticulous in curating their content. He took his inspiration from the renowned 16th century Italian astrologer, Girolamo Cardano, who had risen from obscurity to international fame after his publications intrigued readers with intimate celebrity horoscopes. Cardano’s second major work, published in 1547, a book which Lilly himself owned, had been equally sensational, containing a striking collection of birth horoscopes that ranged from the profiles of philosophers and physicians to that of heretics and criminals.

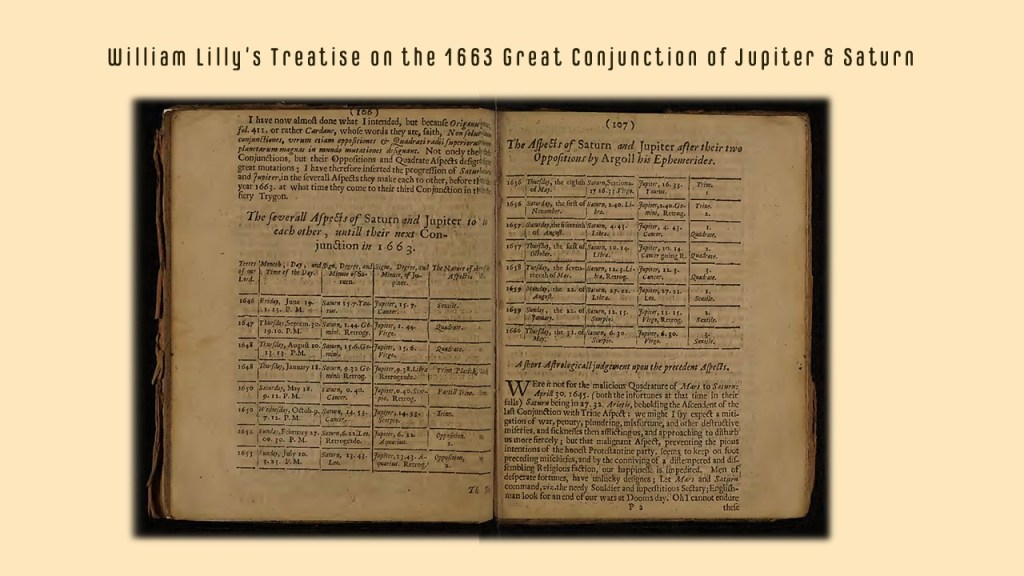

Later that same year, Lilly released England’s Prophetical Merlin, in which he offered predictions concerning the Great Conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn, an apocalyptic-laden event widely perceived to be an omen of England’s future.

From this point forward, his focus shifted increasingly towards political forecasting, initially aligning with the Parliamentarian cause before turning his attention to the fate of the monarchy. But it was during Cromwell’s protectorate that Lilly’s success reached its height, thanks in large part to the relaxation of censorship laws, which, in his words, allowed him to ‘write freely and satirical enough.’ As a result, sales of his almanacs reached a circulation of 30,000.

However, he eventually became disillusioned with the Parliamentarians as well as the censorious Presbyterians and religious zealots, who would often portray astrologers like him as the spawn of the devil. Lilly would later recall that by the time of his 1652 edition of Anglicus, his ‘soul had begun to loathe the very name of Parliament.’ Needless to say, he was imprisoned for almost a fortnight for his remarks.

When it came to his political leanings, Lilly was what Patrick Curry would call a moderate parliamentarian in that he believed in the power of the people, but was not keen on the democratic process being hijacked during the Cromwell years by what he saw as religious zealots and political schemers, only out for their own selfish purposes.

Both during and after the Civil War. Lilly made a series of remarkably accurate predictions about major historical events, many of them concerning the fate of the monarchy and the course of the fighting. Indeed, Lilly became so influential that his astrological insights reportedly played a crucial role in shaping military strategy. Lilly’s role as creator of propaganda was considered extremely important by all the major players. A favourable prediction from Lilly was said to be worth more than half a dozen regiments. During this period, it was not uncommon for both Cavalier and Roundhead supporting astrologers to make contradictory forecasts as to who would win a particular battle, with both sides claiming that victory was theirs. A paper war of astrological pamphlets and almanacs commenced, which appeared to run parallel to the one on the battlefields.

In his Anglicus of 1645, Lilly himself says:

When we have probable hopes of good success beforehand, promised us it might encourage our soldiers to attempt greater actions. If the heavens be averse, more caution must be had.

I find this especially interesting, given that Lilly has Mars in Virgo on the Descendant, which you could interpret as an ability to make accurate predictions about military strategy and the outcome of battles. It also helps to explain his tendency to get into public spats and arguments with his critics and competitors – Lilly could be very cutting and contemptuous of those who he believed either had their facts wrong or were not skilled at what they did.

During the Interregnum, Lilly’s reputation became more complicated. While he had been a staunch public supporter of Parliament during the conflict, some accused him of shifting allegiances, given his propensity to privately read for both Cavaliers and Roundheads, including King Charles himself.

According to his memoirs, Lilly had been consulted several times for advice by emissaries of King Charles in 1647 to 1648, after he was caught and imprisoned by Cromwell’s men. Lilly even claims in his memoirs that he went so far as to have a saw made for the king to help him escape, but the king failed to heed his warnings. Thinking that Lilly was trying to trick him, and so was caught and imprisoned again on the Isle of Wight and beheaded in 1649 – an event that deeply shocked Lilly.

However, there was no escaping the fact that Lilly had predicted the downfall of the Stuart monarchy and been closely associated with parliamentarian figures during the Civil War and Cromwell years. To Lilly, though, it was not a case of political loyalties, but more a case of being true to his art, writing in 1644 that:

I am resolved to stand close to the rules of art without partiality to King or Parliament. I cannot flatter, I will not to mince my judgment and deliver ambiguous stuff is to lessen the validity of the art. I stand upon the honour of my nation.

What is clear is that after the restoration, Lilly took steps to distance himself from his more radical past. He even sought a pardon from Charles II, emphasizing that his astrological work had been impartial rather than politically motivated.

And though he claimed to bear much affection for ‘His Majesty’s person,’ he could not bring himself to lie about what he interpreted to be God’s will when it came to the fate of Charles the First: “But God had ordered all his affairs and counsels to have no success,” and Lilly was quite rightly concerned that this meant the Royalists might shoot the messenger.

His later writings on this period suggest that he was keenly aware of the dangers of being seen as too closely aligned with the losing side, as Ashmole had discovered to his dismay after the Battle of Worcester. Despite all these efforts and his close friendship with Ashmole, a well-known royalist, many continued to view him with suspicion.

Lilly’s true motives remain hard to fathom. While it is fair to say that he delighted in political intrigue, [something we can probably attribute to Pluto in the first House] the question of whether he was a self-seeker with an eye for the main chance, was genuinely neutral in the conflict, or was playing a subtle double game remains a matter of opinion and conjecture.

Ultimately, one could argue that Lilly’s approach was one of survival. A practical Taurus, he adapted to the changing political landscape while trying to preserve his legacy and reputation as England’s foremost astrologer.

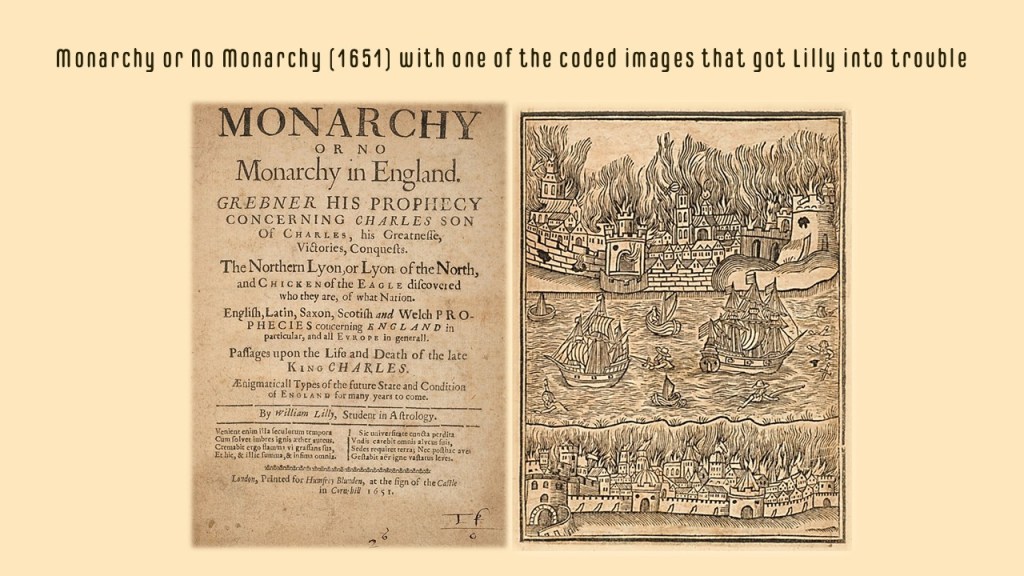

Whatever his motives, one certainly cannot argue with the fact that his astrological foresight was often uncannily accurate. In 1651, he published a set of predictions in the form of coded symbolic images in his Monarchy or No Monarchy. One of these depicted a large fire, later interpreted as a prediction of the devastating blaze that swept through London in 1666. Lilly also foresaw the deadly outbreak of the Great Plague in London in 1665, choosing to leave in late June of that year in order to escape it, once again settling in Surrey, close to his friend Elias Ashmole.

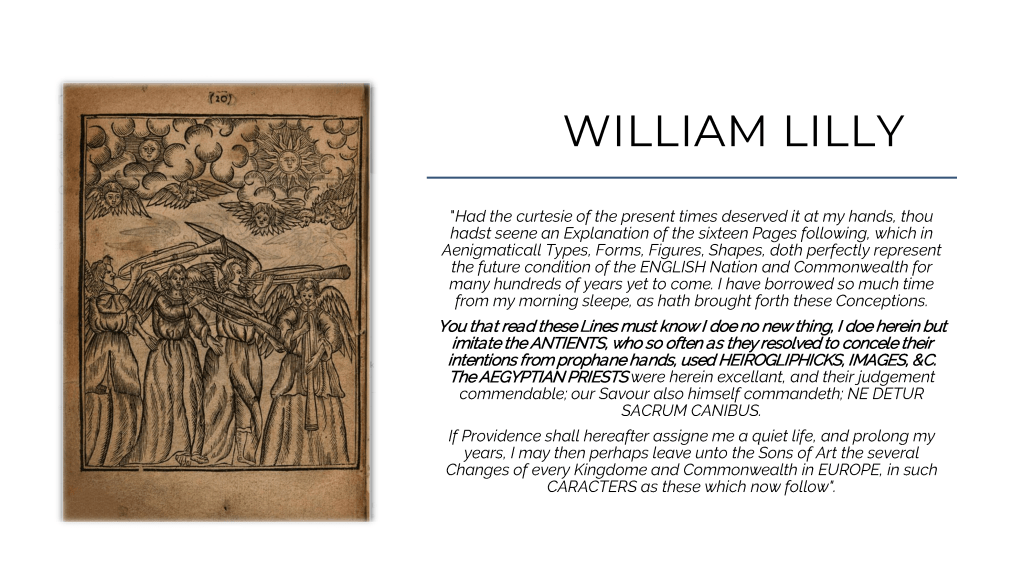

As I mentioned in Episode 5, Ashmole, who enjoyed being a member of mystical initiatory orders and elite secret societies, certainly had no qualms about warning people not to trust every astrologer for ‘the art is a sacred alchemy’ and ‘profound science’ and should not be shared with the uninitiated – a view that the egalitarian Lilly would eventually come to agree with after his own experiences of public criticism and censure from both professional rivals and those in positions of power who wanted to silence him.

As we shall see, Lilly would ultimately came to agree with the elitist Ashmole that sometimes knowledge should be veiled in esoteric code in order to protect it from ‘profane hands’.

Thus, in his 1651 text, Monarchy or No Monarchy, he concealed his forecasts representing ‘the future condition of the English nation for many hundred of years yet to come’ within a series of coded and enigmatic ‘hieroglyphics’. However, even that was not enough to protect him from persecution.

In his autobiography, he recalls the coded predictions he made in 1651, writing that:

[I]n 1666 happened that miraculous conflagration in the City of London, whereby in four days the most part thereof was consumed by fire. In my monarchy, or no monarchy, the next side, after the coffins and pickaxes, there is a representation of a great city, all in flames of fire.

Despite the fact that he had left London for good to escape the plague in 1665, he was summoned back to Westminster in October the following year, to appear before a Parliamentary Committee where he was asked to explain himself with regards to the coded 1651 predictions he had made nearly a decade previously, and was accused of sedition. Luckily, via the intervention of his well-placed and powerful friends like Ashmole and Sir Bulstrode Whitelocke, Lilly once again managed to escape the noose.

Of this episode and the many other attempts by both religious and political factions, to censure and silence anyone critical of them, he wrote in 1644:

How many things would I more deliver, were not my tongue silenced. They were happy that left their judgment to posterity, and concealed them during their lives, they had by this meanes liberty to speake whole truths, we but by peacemeale and fragments, and yet in some danger for that. It is my comfort some will finde my key (sparsim & divisim* Latin for ‘dispersedly, sprinkled here and there’ and/or ‘separately’.). Rex is not always a King, nor homo a man, words have severall explications….

Let us pray for peace.

Coming across this a few years ago, I was struck by the parallels between this period of English history and what is transpiring in places like America, with the press under siege from authoritarian figures and conspiracy theories running rampant on places like social media.

Perhaps we can draw some lessons from Lilly’s time and experiences and do our best not to repeat the same mistakes, whether it comes to striking the right balance between freedom of speech vs censorship; or being more discerning and circumspect about what we share publicly, especially when it comes to complex concepts, controversial opinions or privileged information that could potentially be misunderstood or used in bad faith against us by bad actors or those with mischievous or nefarious motives.

Watch/listen to the full podcast here:

in Episode 7 of the Astro-Insights Podcast, I also discuss both Lilly and Ashmole with Dr Patrick Curry, author of ‘Prophecy & Power: Astrology in Early Modern England,’ which explores astrology during the 17th century – an era that marked both it’s heyday and subsequent decline, as the sweeping changes of the English Civil War and the scientific revolution began reshaping society, politics and culture. Check it out if you’re interested in his take on science vs. astrology, and the different approaches to the celestial art, as practised by these two old friends.

Discover more from AstroInsights Blog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.